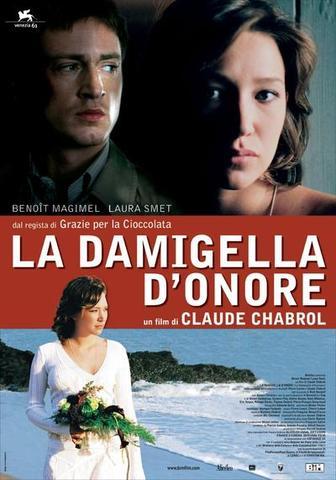

Claude Chabrol – La demoiselle d’honneur aka The Bridesmaid (2004)

A hard-working young man meets and falls in love with his sister’s bridesmaid. He soon finds out how disturbed she really is.

Quote:

the bridesmaid (First Run) Going to a new Chabrol film these days is like sitting down with an old friend who will tell you another one of his stories. Chabrol has been making films since 1958: the latest of his more than fifty features is The Bridesmaid, and another one has already been finished. He has co-written or co-adapted many of his pictures, and he has also played bit parts in some of them (as well as in the films of others). I have seen a lot of Chabrol’s films, and many others must share my sense that much of my filmgoing life is threaded throughout with his work. He has always been a director who felt that moving ahead was at least as important as polishing a single work. This has sometimes let him present less than his best, but the sheer sweep of his career warmly compensates.By now a Chabrol film has become something of a family affair. His wife, Aurore, was the script supervisor of The Bridesmaid; one son, Thomas, plays a small part; another son, Matthieu, wrote the score; his stepdaughter, Cecile Maistre, was the first assistant director. Chabrol’s career even began in family style. In the 1950s, his first wife inherited some money.The two of them were then able to produce his first picture, Le Beau Serge, and they also helped to launch what became, with Chabrol as a leader, the New Wave. Early on, too, he showed his chief thematic interest. With Eric Rohmer–and before either of them had begun directing features–he wrote a book on Hitchcock. Much more than with Rohmer, the Hitchcock influence has often been discussed in regard to Chabrol’s work because he is so continually concerned with crime and guilt and shadowed lives. Obviously among so many films by one man there are variations in quality. An occasional picture, like his Madame Bovary, has been a dud. On the other hand, Chabrol has reached such heights–or should one say depths?–as This Man Must Die, about a man who hunts down the hit-andrun driver who killed his small son, and Landru, based on the same character as Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux. The Bridesmaid ranks high in the Chabrol roster. The first two minutes affirm his mastery. The film opens with a ride down a seaside street in an uninteresting neighborhood that ends at a house in front of which stand some people and a television reporter. She tells us of a crime that has been committed there. As she talks, the image converts into the screen of a television set, and the camera pulls back into the living room of some people who are watching. Thus, gently, we are reminded that crime is ready to appear anywhere, at any time, and that this imminence is nowadays a subliminal part of ordinary lives. In our minds, that opening becomes increasingly freighted as the film unfolds. This is the home of Christine, a widowed hairdresser in her fifties, and her three children. Philippe, in his late twenties, is an executive in a construction firm; Sophie, twenty-three, is soon to be married; Patricia is a typically “difficult” adolescent. All of them are going to dinner that evening with Christine’s boyfriend, Gerard, a man in his fifties, and Christine asks if she may give Gerard the life-size sculptured head of a woman in their garden that her friend has admired. All agree, so they take it along, and we can be sure that this head will figure in what is to come. (The closing credits roll over that head.) Subtle touches abound. Early instance: Gerard had not expected Christine to bring her children to dinner. When they arrive, he swiftly closes the door to the dining room where a table has been set and takes them all to a restaurant. That swift door-closing is characterization by cinematic means. At Sophie’s wedding Philippe meets Senta, the bridegroom’s cousin, who is a bridesmaid. (She adopted her name from The Flying Dutchman.) She is quiet but not reticent. This is quickly demonstrated when she follows Philippe home–he had to leave the wedding early–and very soon maneuvers him into bed. Their affair continues at Senta’s house, which she owns. Though it is large, she lives in the crummy basement. On the floor above, her stepmother, a dance teacher, practices the tango with her partner; above that are large rooms filled with white-sheeted furniture. Senta’s cool-hot intensity, the force with which she tells Philippe that she has been waiting for him all her life, that she loved him at first sight, is intoxicating to Philippe and lifts him to her state of passion. In the course of time she recounts, truthfully or not, her lurid past in other countries. She says that she is now a would-be actress in (nearby) Paris and that, when she can’t get acting work, she poses for porn photos. He accepts all these matters as part of her unique being. After they are deeply involved with each other, Senta tells Philippe that they have reached the plane where each of them must kill someone to prove the sublimity of their love. This pseudoNietzschean formula, elevating them beyond good and evil, at first amuses him. But she is serious, and he is so fevered to please her that he pretends compliance. Next day a murder is committed down on the docks, and, using it as a convenience, he boasts to her that he did it. She believes him. She then feels that she must fulfill her obligation. The screenplay, adapted by Pierre Leccia and Chabrol from a novel by Ruth Rendell, dramatizes intoxication by passion–how it can take lovers, particularly when one of them is already quite strange, into places that had been unimaginable. Chabrol surrounds this affair with the quite mundane troubles of Philippe’s family, and these troubles have a double effect. They seem small compared with his consuming affair with Senta, and they also seem precious as fingerholds on normalcy. Chabrol also makes a character out of Senta’s weird house itself, where the tango sometimes goes on above the darkening lovers. Chabrol insured the power of this dangerously difficult film with perfect casting. The two lovers are so well acted that their story–and its finish–are incredibly convincing. Benoit Magimel, who was Isabelle Huppert’s young lover in The Piano Teacher, gives heat to all the shades of feeling that come Philippe’s way. Laura Smet, unbeautiful but sexy, creates a Senta who is driven by forces that she can’t control and is glad of it. Charming Aurore Clement plays Philippe’s mother, just good enough to be true. Matthieu Chabrol’s score winds enticing filaments of sound through the film. Chabrols, onward! Send us your next picture, please, along with word that you are making another.

Language(s):French

Subtitles:English, French